texts about zs

Zdeněk Sýkora in Select Society is a loose follow-up on the 2011 exhibition titled Born in Louny, which primarily focused on the Louny aspect of Sýkora’s life and work (landscapes, Gardens series, friends in Louny and places where he painted). At that time we aimed to present Zdeněk Sýkora in an international context, an arena he entered in 1965, when he participated in an important contemporary art show in Zagreb titled New Tendencies 3. This was followed by tens of group exhibitions where he presented his work alongside other famous 20th century artists and artists whose acclaim did not come until more recently, representatives of abstract, Concrete, Constructivist and computer art. Many became Sýkora’s close friends, visiting one another and even exchanging works with him. The select set of paintings, objects and prints also includes such names as Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse and François Morellet. The exhibition also features study materials available to visitors – catalogues from group exhibitions and books focused on individual artists. We believe this project will expand understanding about the inclusion of the Louny native’s oeuvre in the international context of fine art.

As the title suggests, the exhibition presents Zdeněk Sýkora in select society. This society is “select” in several senses of the word. Names like Max Bill (1908–1994), Richard Paul Lohse (1902–1988), Kenneth Martin (1905–1984), François Morellet (1926), Jan van Munster (1939), Manfred Mohr (1938), Manuel Barbadillo (1929–2003), Hiroshi Kawano (1925-2012), Georg Nees (1926), John Roy (1930–2001), Ad de Keijzer (1923–1997), Ad Dekkers (1938–1974), Karl Prantl (1923-2010), Ewerdt Hilgemann (1938), Ryszard Winiarski (1936-2006), Christian Megert (1936), Horst Bartnig (1936), Andreas Brandt (1935), Christoph Freimann (1940), Max Mahlmann (1912–2000), Wilhelm Müller (1928–1999) and Gudrun Piper (1917) are certainly among the select, recognised names in art in the latter half of the 20th century. If one would want to find some sort of unifying category and single label for their work in art terminology, perhaps it could be called Concrete art (as defined by Max Bill in 1947). It is primarily characterised by its search for objectiveness (as opposed to subjectiveness), using constructive or mathematical methods, searching for order (randomness may also be a methodology applied in the search) and rules of composition, and resolving relationships between basic means of expression in fine art such as colour, light, movement, volume and space. Each of the above artists addresses their own little task in this field; each came up with and assigned their task; each has their own obsession. The result of their creative experimentation is an authentic, expressive style. Though art trends are turning in different directions, Concrete art has been alive for over fifty years now and more artists are joining the movement, despite the fact that other -isms that are just as old have long sunk into oblivion. François Morellet, for example, remains a leading French artist; in 2010 no one else would have been entrusted with designing and installing new windows at the Louvre.

The society of artists we are presenting at the exhibition was selected based on specific criteria: Zdeněk Sýkora had met them at exhibitions at museums and galleries; he was selected with them for several projects, exhibitions and artist’s books of prints; he befriended some of them and they visited one another, often right here in Louny. It is very important for an artist to belong to this international society: it strengthens their confidence and sense of belonging, confirms that they’ve embarked on the right path and helps them battle provincialism and small-mindedness. But belonging to such society is hardly a matter of course or something that happens overnight. I looked for the beginning of this story, Sýkora’s first steps into the world. Because our life together lasted thirty years, I couldn’t simply rely on my own memories to untangle this wound-up ball of relationships, as the first art contacts across the country’s borders date back to as early as 1964. So I had to delve into our voluminous archive, read through correspondence and look through tens of catalogues and hundreds of photographs. Although I have personally experienced many meetings and new relationships at Sýkora’s side since the 1980s, various diary entries and notes helped most in putting the events into chronological order.

The crucial year seems to be 1964, when Zdeněk Sýkora first presented his Structures to the public at an Umělecká beseda exhibition in Prague and when, in collaboration with mathematician Jaroslav Blažek, he created his first Structures with the use of a computer at his new studio in Louny; when the first exhibition of the Křižovatka (Crossroads) art group was held in Prague (Sýkora exhibited Structures, Fremund landscapes, Kolář “evident poetry”, Malich objects, Mirvald ink “splotch blotches”); when Jiří Kolář was on exhibit in Louny and the idea came to establish the Benedikt Rejt Gallery; when several Czechoslovak art shows were organised for European museums and Sýkora’s work was also selected; when he started to work on his habilitation about the relationship of colour and space in contemporary art; when he first set out for Paris with Jiří Kolář and Karel Malich (he also visited Šíma’s studio); and when he attended a meeting between writers and artists in Alpbach, Austria. After years of isolation, new opportunities were opening. In 1965 he accepted an invitation to Zagreb, Yugoslavia, to attend the third continuation of (what is now a very) prestigious exhibition of New Tendencies in European art. Two of his Structures – a painting and sculpture from 1963 – travelled by train, while Zdeněk Sýkora and his friend from Louny, painter Vladislav Mirvald, got into their car and set out on the long journey. We have many pictures from their trip in the archive, but just one photo from the installation. But from the catalogue we know it was here where Sýkora’s work first encountered Morellet. Back then the two had no idea that they and their work would be so close. Whereas Sýkora used Structures to stipulate strict rules and for him objectivity meant suppressing chance solutions as much as possible, François Morellet was already a representative of art associated with randomness. For the first time, Sýkora’s works hung in the company of Martin, Piene, von Graevenitz, de Vries, Böhm, Riley, Colombo, Vedova, Bonies, Staudt and Gerstner, whom he later often met at contemporary art shows. Equally decisive for Sýkora’s entrance on the international art scene was his participation in a small, yet very important exhibition: Constructivist Tendencies from Czechoslovakia, which was held at the University of Frankfurt. This was organised by German journalist, art expert and curator Hans-Peter Riese, who knew the Czech environment and artists very well (another visitor to Louny, of course) and did much to promote Czech art.

Sýkora’s participation in the Zagreb and Frankfurt exhibitions (as well as in others) and especially his innovative contribution towards the investigation of structures, using a computer as a tool to assist in constructing structures, opened the door to other museums and private galleries, especially in Germany. His first contacts with gallery owners Heinz Teufel and Heidi Hoffmann date to that period. The first foreign collectors noticed him, museums purchased several paintings to add to their collections and the first screenprints were printed. Interest from around the world is demonstrably reflected in growing correspondence: we find cards and letters from various artists (Domela, Franke, von Graevenitz, de Vries, Malina), invitations to symposia and exhibitions, many requests for texts and photographs, the Venice Biennale invites him to write a thesis about his work, the international journal Leonardo becomes interested in him. As a representative of Czechoslovakia he (along with Jiří Kolář and Milan Dobeš) is selected for Documenta 4 in Kassel in 1968 – at the time, this was the greatest recognition a contemporary artist could receive. Additional important exhibitions followed this. In 1969 he travelled back to Zagreb to participate in Tendencies 4, though this time with Josef Hlaváček, who was scheduled to talk at the symposium. He exhibited computer Structures here and the museum in Zagreb got one to add to its collection. Two very important biennials in Nuremberg followed this, then Paris, Tokyo, Bradford and Avignon, and thanks to Meda Mládková, an exhibition of prints in Oregon and Washington. New Tendencies in Zagreb was an especially rich display of various opinions and ideas, presenting new trends, concepts and interdisciplinary contexts. Lectures, symposia and discussions between artists and mathematicians, composers, authors and scientists were an integral part of the event; the names of additional representatives of contemporary art were added – including pioneers in computer art (they will meet again a few years later, at Album SDL). But what is most important: Zdeněk Sýkora could participate in these events in person and strike up friendships, exchange experience and compare his and others’ opinions. He enjoyed travelling, had no problems communicating and spoke a number of foreign languages (he was fluent German and French and studying English as he won a Ford Scholarship at the time; unfortunately, in 1969 he was no longer allowed to leave the country). He patiently replied to various requests from around the world, wrote texts and sort of personal manifestos, and gave several interviews. The question is how he could manage to juggle all this because he was also working on two major architectural projects in Prague (wall tiles on Jindřišská Street and on the ventilation shafts in Letná plain in Prague), painting tens of Structures – and one mustn’t forget that he was also a university lecturer in Prague and became an associate professor. In any case, it seemed that nothing stood in the way of his career as an international artist: he was invited, positively reviewed, honoured and appreciated. Zdeněk Sýkora became a member of select society.

But in 1969 his trips abroad came to a long halt. Despite this, the world didn’t forget him and his works continued to appear at important exhibitions, though it was difficult to loan them out. In 1972 Canadian artist, publisher and gallery owner Gilles Gheerbrant, who was the publisher of the now legendary computer artist’s book of prints titled Art ex Machina (1972), featuring the text of no one less than Abraham A. Moles, wrote a letter to Zdeněk Sýkora inviting him to attend an international computer art exhibition in Toronto sponsored by a Canadian company specialising in computer data processing. One year later he invited him again to participate in the Album SDL (1973) project. This project was initiated by a Canadian software company and the artist’s books of prints were not put up for sale, but rather distributed to corporate clients as gifts. The committee selected nine artists, pioneers in computer art, from around the world: Manuel Barbadillo, Hiroshi Kawano, Kenneth C. Knowlton, Manfred Mohr, Georg Nees, John Roy, Roger Vilder and Edward Zajec. And Zdeněk Sýkora. The book contains not only prints of artworks, but also programmes and mathematical descriptions of the processes used by individual artists. The U.S. magazine Datamation, which had a circulation of 100,000 at the time and was read by computer enthusiasts worldwide, reported on the edition. The prints were to be signed in Canada with the company covering travel expenses. It probably is not surprising that Sýkora was the only artist who could not come. He signed the book in Prague, where the gallery owner sent a courier. In this book he made his first visual encounter with Manfred Mohr, whom he first met in person in Amsterdam in 1989. We later met him and his wife, mathematician Estarose Wolfson, at Heinz Teufel’s gallery in Mahlberg. In the 1980s Manfred Mohr, a leading representative of computer art, was one of the first artists who wished to have a picture by Sýkora. Gilles Gheerbrant would be the mediator. We did not meet him until 1988. Back then he explained to us that on his way from Vienna, he got off the train in Brno to view the famous Functionalist architecture and to his surprise he came across posters promoting the Zdeněk Sýkora retrospective exhibition at the Brno House of Arts. He rushed to Louny from Brno. That marked the start of our friendship. We had in him another bearer of good tidings who linked us with the rest of the world. Though the exchange of pictures with Manfred Mohr never happened, our relationships remained friendly and filled with admiration and respect. Manfred and Estarose also visited us in Louny and marvelled at the view of the Central Bohemian Uplands from the studio. A couple of years ago we introduced them to our friend, Miroslav Velfl, who added Mohr’s works to his collection of Concrete art. For an exhibition in Louny we borrowed two paintings from Velfl’s collection, P-021/387 (1970-87) and P-411-D (1988), which feature the artist’s typical style.

Dutch artist Jan van Munster also wished to have a Sýkora painting, specifically Lines No. 45 (1987), which we gave the working title of “Bat”. Because artists as a rule do not buy their colleagues’ works, we exchanged the painting for a neon object called Between plus and minus (1981). This work was typical for the period when the artist’s personal theme was the tension between plus and minus, between the concept of a warm world and a cool world of neon, and as always it was associated with his personal parameters (height in this particular case). As he wrote me in his reaction to the fact that he had been selected for this exhibition, Lines also occupy a place of honour in his new home. We have known each other for over twenty years and met at Art Affairs Gallery in Amsterdam. The owner of the gallery, Antoinette de Stigter, isn’t an artist, but her role in Zdeněk Sýkora’s artistic life must be mentioned. Above all, in 1974 she asked him to participate in a symposium in the small Dutch city of Gorinchem, where she was in charge of the a private cultural centre. The aim of this event was to “bridge the gap between the local populace and art through intensive and direct confrontation with fine art in a familiar environment”. Sixteen artists from throughout Europe had been invited – Kenneth Martin, François Morellet, Ad de Keijzer, Marinus Boezem, Ad Dekkers, Karl Prantl, Ewerdt Hilgemann, Getulio Alviani, Ryszard Winiarski, Panamarenko, Kees Franse, Christian Megert, Lev Nusberg, Uli Pohl, Herman de Vries and Zdeněk Sýkora – to create a design for the city’s public space. They were to personally participate on site in implementing the project, which was sponsored by local firms. Once again Zdeněk Sýkora could not leave his country; his department colleagues feared that he would later have a negative influence on students. Based on a design he sent by post, though, the entrance of a pedestrian shopping zone was paved with tiles in 1974 (restored and relocated in 2005). As a bonus to the entire event, a catalogue and an artist’s book of prints, bringing together all of the artists’ work and simply titled Symposion Gorinchem (1975), were published. Sýkora also couldn’t receive and sign this book on location; instead, the Secretary of the Symposion Foundation and Dutch tennis player Siebe Huizinga, who was playing in a tournament in Prague, had to bring it here. Antoinette de Stigter was so keen about Zdeněk Sýkora’s work, she offered him an exhibition in Kunstcentrum Badhuis as early as 1977. But the conditions laid out by Art Centrum, which had the monopoly on exports of art from Czechoslovakia, were entirely unacceptable to her. Nevertheless, she did not give up and in 1978 she set out for Czechoslovakia to visit Zdeněk Sýkora at his studio. She thus became the first gallery owner to see Lines with her own eyes (the first Lines were created in 1973). As she later noted, “I was surprised by the work that he, in maximum isolation and with fascinating concentration, had carried out year after year.” Unfortunately, Zdeněk Sýkora could not even attend the very first exhibition of his Lines (1979), moreover a solo exhibition, because he was still employed at the faculty in Prague and his colleagues had not changed their minds. The exhibition was successful and the Lines took on a life of their own – they travelled to Switzerland and later to the Josef Albers Museum in Bottrop, Galerie Heinz Teufel and Art Affairs, and in 2005 all the way to the Centre Pompidou in Paris and Museum der Moderne Salzburg. At the prestigious Herbert-Boeckl-Preis ceremony for lifetime achievement at Museum der Moderne, the story of the Lines seemed to come full circle: In his laudation, Austrian collector and art expert Dieter Bogner (regular visitor of exhibitions in Gorinchem) recalled how one time back in 1979, while travelling to Rotterdam with his wife, Gertraud, by chance they made a detour via Gorinchem – where they first saw Sýkora’s Lines and were immediately smitten. He soon bought a painting which is now in the collections of Museum Moderner Kunst (mumok) Vienna.

After the Netherlands, the first journey the Lines took was to Neuchâtel, Switzerland, to Galerie Média and gallery owner-publisher-printer Marc Hostettler. He was especially known for his editions of prints. He published many artists’ screenprints, including Swiss classics Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse, and he arranged Sýkora’s brief meetings with the artists. He also published several prints by English artist Kenneth Martin, whose lines have much in common with Sýkora’s. Martin also worked with a system and assigned colours and directions to numbers. He expressed great interest in Sýkora’s oeuvre and we were invited to London. Regrettably, we never met, but we have two beautiful screenprints in our collection: Pier and Ocean and Venice (both 1980), in which the artist “revealed the secret” to his system and which demonstrate just how close the two artists’ thought processes were. We also borrowed an oil painting titled Chance, Order, Change 4 (1978) from a private collection. The painting is the result of the investigations shown in the screenprints. In 1980 Marc Hostettler published the first artist’s book of screenprints by Zdeněk Sýkora, and the next year he included his Lines in an important, four-part exhibition titled Cycle Média, where the Lines ended up next to pictures by Bill and Morellet. Everything has been documented in a beautiful catalogue. The gallery owner courageously bet on Sýkora at Art Basel and exhibited Lines in a one-man show. He later initiated a solo exhibition at the museum in Chambéry. By then times had changed: Zdeněk Sýkora, aged sixty, retired mid-semester and in a year he was allowed to travel outside the country. His return among European artists was joyous, resulting in meetings with old friends and starts of new friendships. He returned from his first trip in 1981 filled with optimism and confidence as he could see firsthand that his work stood up next to artists he held in such high regard, and moreover, he received recognition from several notable critics. He dove into creating more Lines with gusto and interest. Recognition motivated him.

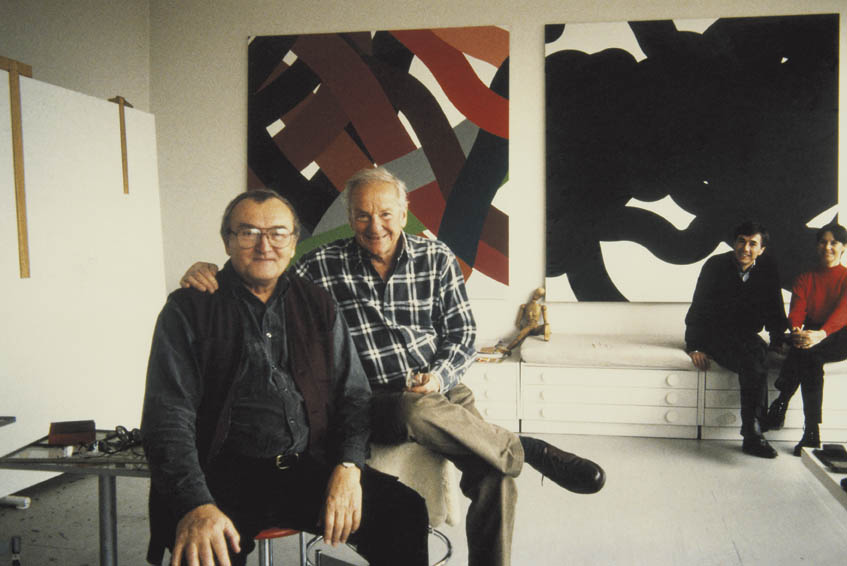

Respect and admiration was also behind François Morellet’s invitation to come to his beautiful house in his hometown of Cholet in 1983. I enjoy recalling this first meeting, the Morellets’ hospitality and honest interest, cheerful and attentive François and his wife, Danielle, who became an example for me in working together with my husband and whose archive absolutely astounded me. And their son, Frédérik – he gave us albums featuring the minimalist music of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. François showed us his studio. At the time he was going through a period he called “geometree”. Both artists were united not only in their opinion about art, but also humour and optimism about life, and became very close. Although we did not see each other that often, our relationship was strong. If they could not go to an exhibition opening in person, we always received a card in the post. He also visited us in Louny. They, too, were mesmerised by the landscape, the cathedral roofs and of course Sýkora’s pictures. It was François who asked for an exchange. Thanks to this, we can exhibit his work bearing the beautiful name of Tableau incliné à 15° avec 4 droites de néon dont 3 sont parallèles à ses côté et une parallèle au sol (1993) in Louny. In turn, he had his photo taken in front of our painting Lines No. 73 (1990), which we nicknamed “Ice Cream Man”. As a bonus we gave him an equation to calculate the individual points on an arc, because he, too, dealt with curved lines in his work. Many years later, François Morellet expressed his feelings in a letter to the French ambassador and asked him to read it aloud at the memorial service for Zdeněk Sýkora held at the Kampa Museum on 20 July 2011: “It does not cease to amaze me that many years before we met, each of us, alone in our remote towns – he in Louny and I in Cholet, fervently tried to find a way to achieve distance from our works. Unlike the infinite number of artists whose work reflects their ‘deep inner selves’, our art could essentially develop independently of us. This was a courageous attitude and commercially quite suicidal. Fortunately we had galleries that were inclined toward us, like Art Affairs in Amsterdam and Média in Neuchâtel. Both protected and often connected us. Today I am very sad and touched by the loss of such a remarkable partner in crime…”

Respect and admiration was also behind François Morellet’s invitation to come to his beautiful house in his hometown of Cholet in 1983. I enjoy recalling this first meeting, the Morellets’ hospitality and honest interest, cheerful and attentive François and his wife, Danielle, who became an example for me in working together with my husband and whose archive absolutely astounded me. And their son, Frédérik – he gave us albums featuring the minimalist music of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. François showed us his studio. At the time he was going through a period he called “geometree”. Both artists were united not only in their opinion about art, but also humour and optimism about life, and became very close. Although we did not see each other that often, our relationship was strong. If they could not go to an exhibition opening in person, we always received a card in the post. He also visited us in Louny. They, too, were mesmerised by the landscape, the cathedral roofs and of course Sýkora’s pictures. It was François who asked for an exchange. Thanks to this, we can exhibit his work bearing the beautiful name of Tableau incliné à 15° avec 4 droites de néon dont 3 sont parallèles à ses côté et une parallèle au sol (1993) in Louny. In turn, he had his photo taken in front of our painting Lines No. 73 (1990), which we nicknamed “Ice Cream Man”. As a bonus we gave him an equation to calculate the individual points on an arc, because he, too, dealt with curved lines in his work. Many years later, François Morellet expressed his feelings in a letter to the French ambassador and asked him to read it aloud at the memorial service for Zdeněk Sýkora held at the Kampa Museum on 20 July 2011: “It does not cease to amaze me that many years before we met, each of us, alone in our remote towns – he in Louny and I in Cholet, fervently tried to find a way to achieve distance from our works. Unlike the infinite number of artists whose work reflects their ‘deep inner selves’, our art could essentially develop independently of us. This was a courageous attitude and commercially quite suicidal. Fortunately we had galleries that were inclined toward us, like Art Affairs in Amsterdam and Média in Neuchâtel. Both protected and often connected us. Today I am very sad and touched by the loss of such a remarkable partner in crime…”

Paradoxically, Marc Hostettler was also at the beginning of the rediscovery and success of Zdeněk Sýkora’s work in the German environment. His belief in the power of Sýkora was also caught by the director of the Josef Albers Museum in Bottrop, Ulrich Schumacher, who in 1986 decided to hold a large retrospective exhibition of his work. This exhibition clearly demonstrated that Sýkora still belonged to select society. Because the latter half of the 1980s is characterised by a gradual thaw in the political climate and the renewal of old contacts, Zdeněk Sýkora once again received many offers to exhibit, attend symposia, publish screenprints and travel invitations. From the 1990s he then got to fully enjoy his success (once again we could name major European museums, such as those in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Nuremberg, Barcelona, Mönchengladbach, Ludwigshafen and others). Heinz Teufel started to gain ground as a gallery owner, reappearing in Prague in 1987 and offering to work together: he was prepared to represent Sýkora and protect his interests on the European art market. Over the course of twenty years Teufel developed from an art dealer who had opened a small gallery in Koblenz focused on Concrete and Constructivist art, exhibiting Miloš Urbásek, Jan Kubíček and other artists, into an influential gallery owner in Cologne whose exhibitions set the tone in this field of art. Among others he exhibited classics of Concrete art such as Josef Albers, Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse, Mario Nigro, Camille Graeser, Aurélie Nemours, Jo Delahaut, Max Mahlmann and Gudrun Piper, as well as a younger generation of artists, like Bridget Riley, Heijo Hangen, Wilhelm Müller, Bob Bonies, Hansjörg Glattfelder, Andreas Brandt, Manfred Mohr, Horst Bartnig, Christoph Freimann and, since 1988, Zdeněk Sýkora. To celebrate the gallery’s thirtieth anniversary and gallery owner’s sixtieth birthday, eight artists from his “stable” decided to publish Zum 60. Geburtstag Heinz Teufel (1996), an artist’s book of prints, as a thanks for his work, commitment, infectious vitality and the joie de vivre he impressed on visitors to his legendary exhibition openings which not only offered exquisite art, but were also a cultural experience for epicureans. Heinz and his wife, Anette, also stayed in Louny many times; they even wanted to establish a branch for their gallery and create an international centre for modern music and fine art here. As the early Nineties were not auspicious for art visionaries, the gallery was established in Dresden instead. It is too bad. Louny, conductively combined with the Benedikt Rejt Gallery, which has been focused on Constructivist tendencies since the 1960s, could have become a place where Concrete art devotees would enjoy returning again and again. Heinz Teufel was a great fighter who didn’t give up on his dreams; his sense of humour and élan remained with him even after he learned he was seriously ill. He was the type of person who could see his plans through to the finish. He was precise, cared about every detail, did much for his artists and we learned much from him. In 2006 he still managed to shoot a documentary about his gallery and his four artists. Zdeněk Sýkora’s hometown played an important role in it because even Heinz Teufel knew how important Louny was to Sýkora.

So how could an artist from a small Bohemian city make it into select (international) society? Most of all he must have a message and be passionately absorbed in it. He has to work hard and believe in himself. He may not be afraid to appear in public with his work and defend his ideas, even if he’s up against everyone. And then it’s important to have good fortune when it comes to people. If his art appeals to someone who will stand behind it, who will invest energy into connecting it with other artists and admirers, who will be able to “infect” kindred spirits, he’s home and dry. Although Facebook did not exist in the 20th century, people still shared the same values, helped one another and promoted their friends’ works. Zdeněk Sýkora was quite courageous and original, hard-working and friendly, but was also lucky to have such people. As a result, his oeuvre has become a natural part of international society.