texts about zs

As far as I know, originally there were no plans to organise an exhibition of Zdeněk Sýkora’s works in the artist’s hometown for his eightieth birthday. As Benedikt Rejt Gallery also started to host short exhibitions, however, the artist couldn’t turn them down. Sýkora had made a name for Louny among a certain group of people, especially abroad.

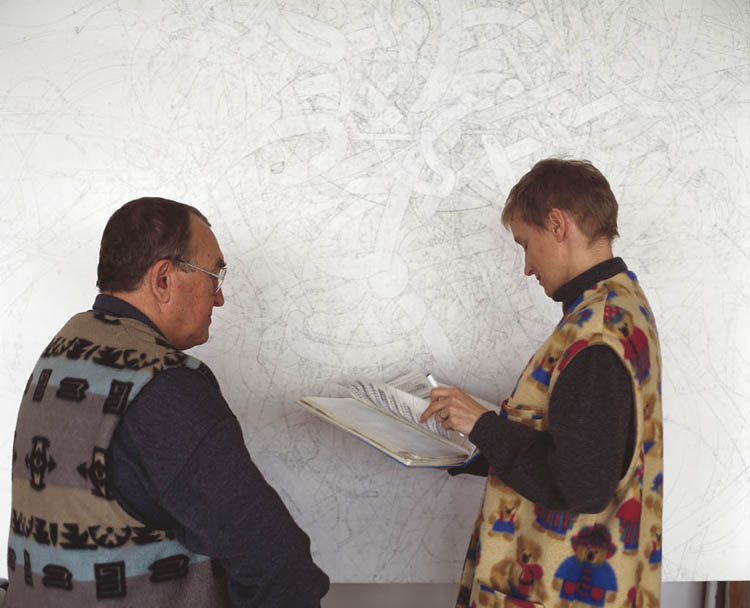

Given the limited ground-floor space, with four large stalls and two polyhedrons on the fringes off to the right and to the left in back, it was clear that the exhibition could not even attempt to show the artist’s collected works, but rather a narrow selection of exhibits. The artist and his wife, Lenka, who have truly worked together for fifteen years now, took charge of the preparations. The result is a strictly selective, but succinctly chosen retrospective that was made possible by the fact that both Benedikt Rejt Gallery and the artist himself own many crucial works.

The curators chose to exhibit the works in reverse chronological order, but due to the open space, visitors can go back as they wish and repeat certain situations and relationships over and over again. I am not sure if anyone still needs to be convinced to understand the significance of Sýkora’s oeuvre; the presentation in Louny shows the singularity of his oeuvre in each phase and in its entirety, created in over forty years of intense work. The exhibition does not start with the artist’s actual beginnings; one could say that it indicates the artist’s path towards abstraction. The oldest section is Gardens from 1959, when, as he always explains, his encounter with the Matisse collection at the Hermitage in Leningrad helped him make a radical shift in his painting. Of course, Sýkora was prepared for this shift, starting with his Cubist endeavours in the 1940s and especially his interest in using blotches of colour to construct a picture.

The fact that Sýkora is fundamentally a painter, an artist for whom the painted picture means everything, could be viewed as the leitmotiv of the entire exhibition. Matisse’s lesson led to a radical freeing of colours and morphologies, launching several years of intensive work and progressing through several stages to his discovery of increasingly autonomous methods for painting compositions. This took place over just five years, from 1959 till 1964, as the exhibition shows – and one must realise what the context of Czechoslovak art was at the time. Tendencies toward abstraction did appear in the work of various artists, but in the majority of cases this was Art Informel and existentially-oriented art. Sýkora strove for the exact opposite: painting as a positive reflection of the world and human life. The colours in his Gardens became increasingly independent; by 1960 they had become loose compositions of round, irregularly bordered and articulated surfaces. Gradually this geometric structure was developed further, and in 1962 he his compositions contained surfaces delineated by clear lines. In the details they are still sometimes marked by a previous interest in brushwork, but over time they became less and less personal.

The surprise of the exhibition is Red Squares (1962), in which Sýkora hints at horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines as a determinative compositional principle. Like his well-known paintings Red Arrow and Composition – Red, Blue, White (1962), the first Czech paintings that lack brushwork and use the counterpoints of several radically simplified geometric surfaces circumscribed by straight lines as an autonomous principle, Red Squares foresees his interest in combinatorial composition. At the time this was the most radical thing that could be seen in Czech painting, but Zdeněk Sýkora’s stream of thought continued to move forward: he realised that a simple geometric element could be a new syntactic element in a more complex unit, subject to new, rational rules of composition. He started to create Grey Structure (1962-63). At the exhibition, the painting is conspicuously installed at the end of the geometric compositions and essentially concludes the entire older section of the exhibition.

This makes it clear that the second half of the exhibition must comprise a selection from the over 200 works that have been created since that time. Grey Structure is a pivotal work of Czech art. It was the first Czech painting to use combinatorics and stimulated serious discussions on whether this sort of technique was native to the country. It is a very beautiful painting. The combinatorial composition, still intuitive, is led by a desire to find various visually-differentiated substructures that can be perceived as an autonomous aesthetic quality.

Because Zdeněk Sýkora wanted to withdraw further into the background, in 1964 he started to work with mathematician Jaroslav Blažek, who helped him get a computer involved in the selection of combinations. This was Sýkora’s next pioneering work, which is internationally respected to this day. The exhibition offers evidence of this path in several of his most important paintings, starting with his classic black and white semicircles and first experiments with vivid colours (1965).

Though fundamentally a painter, Sýkora also thought about space. The result was three-dimensional combinatorial configurations; the most varied and uneven of them was aptly installed in the odd small polyhedral space. His work also included the spatially curved Topological Structure (1969) and a combinatorial configuration of three-dimensional elements (Vertical Structure, 1967). Visitors find all this at the exhibition after they have discovered Macrostructures (1972), which starts to call attention to the linear connections among the contours of individual segments.

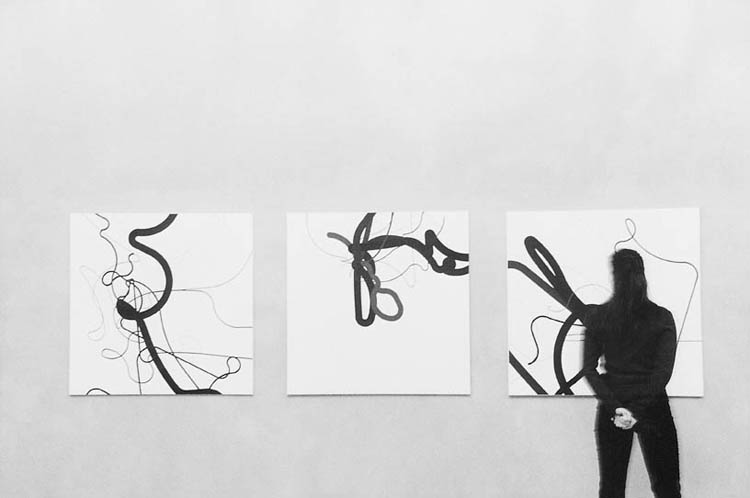

This logically led to Lines, which were created from 1973 to the present. Though only a quarter of the exhibition is devoted to Lines, his works from this period are effectively displayed in excellent examples, starting with the first, very simple Lines, advancing to complex layers and on to the last paintings, formed by defining the centre or centres. Lines are also true to the painter’s visualisation of the basis, and are again created with a computer. The computer randomly selects the specifications entered (over the years, the number of specifications increased). Each picture essentially “depicts randomness” while respecting certain input (such as a colour chart or other defining principle). Of the approximately 200 Lines in existence, only a few could be displayed in Louny. Yet these pictures are exceptionally serious, and moreover, the Lines from recent years may surprise many viewers as they form a rich, varied, and yet evidently internally connected whole.

For some this may mark the start, for others the end of the exhibition. But for all it is proof that Zdeněk Sýkora found an incredibly inspiring principle for articulating picture composition that is in a class of its own. As a result, we view pure randomness as an order equally powerful to the order immanent in man, nature, the cosmos or even God, based on our own disposition that we bring with us to the exhibition – various others have also interpreted the artist’s pictures this way. In the end, it is just a question of terminology; what is important is the order in the picture Zdeněk Sýkora discovered. He found it in the combinatorial structures and radical geometric structures that preceded it, and he found it in the autonomy of the colourful blotches of his Gardens. His sensitivity as a painter is combined with a radicalism with which he successfully used the most cutting-edge tool of the period to the benefit of his paintings, at a time when this concept was unique.

As a result, he discovered a new world of painting – and he was able to create not only his magnificent oeuvre, but also foster the existence of painting, the existence of the picture, at a time when people were interested in other media. In the other tiny room there is a projection that intersperses photographs of young Zdeněk Sýkora heading out to the “open air” to paint with an outline of the river, evoking memories of old radio reports about water levels on Czech rivers, including the magical Ohře (Eger) in Louny… The curve is similar to the curves in Sýkora’s paintings, but it also bears proof that there are others – and they are unrepeatable.